MORE ABOUT LARRY

Larry Griffin was born in Independence, Kansas—a town where the streets ran straight and the horizon stretched wide, but where the pulse of the town had begun to slow. Nestled at the edge of the Ozarks, Independence was framed by rolling hills and dense forests more typical of the east than the wheat-flat west. The town carried the weight of history in its early 20th-century buildings and the echoes of pioneers and settlers. Main Street ran six lanes wide, the central artery of a once-vibrant and prosperous community. By the time Larry came of age, the momentum had started to fade. Industry was pulling back. Families were moving on. Independence was still a good place to grow up—but not necessarily a place to stay. For Larry—“Lawrence” to his schoolmates—the future seemed like something you had to go elsewhere to find.

Riverside Park stood as a kind of last bright echo of what had been—a place of civic hope and community pride. The heart and spirit of Independence. There were picnics there, concerts in the bandshell, and the local football team—the Bulldogs—riding high on a near-mythic 49-game winning streak from 1957 to 1962, under their legendary coach, Kayo Emmot. The park held pools, a locomotive, a jet fighter on a pedestal, a river, and a sense of old-fashioned pageantry now mostly gone from the world. On summer evenings, as the sun slipped behind the trees, you could almost hear the notes of “Moonglow” in the air—like that park day in William Holden’s Picnic, where everything shimmered and the world was still innocent.

Larry developed his dreams of the Nürburgring while driving the winding roads near Elk City Lake—roads that carved through the Kansas hills with a rhythm that echoed something far greater. The Nürburgring itself was a legendary, 12.9-mile racetrack cut into the Eifel Mountains of Germany, notorious for its blind corners, punishing elevation changes, and near-mythic difficulty. Known as the Green Hell, it was motorsport’s most unforgiving crucible—part proving ground, part executioner. In Larry’s heart, it was more than just a racetrack—it was a proving ground of courage, where men measured themselves against speed, steel, and the quiet fear of not being enough. This would become part of his automotive reverie.

It was on these roads, far from the highways and tracks he would later conquer, that the foundations for his dreams were laid. These early drives, with their sweeping bends and changing rhythm, stirred something in him. They offered not just escape but possibility—a glimpse of another life, measured in apexes and throttles, where everything mattered and everything made sense.

Even as a boy, Larry seemed destined for elsewhere, drawn to the idea that the road could offer something cleaner, sharper, and freer than the lives unfolding quietly around him. He first learned to drive in his mother’s 6-cylinder, 1957 Ford two-door—a car that would become more than just a means of transportation, but the first step toward the world he longed to explore. His first job, delivering flowers for Ahmann’s Flower Shop, gave him his first taste of meaning on the road—not the open road, but the beginning of something that felt like it. At 17, he began hot-rodding his mother’s new 1963 Ford Galaxie 500, a car that became his canvas for becoming himself — and for chasing the kind of freedom that kept the darkness at bay.

Lawrence was shaped by contrasts. His brilliant, sharp-tongued mother nurtured his eye and sharpened his pen. Summers at camp as a child introduced him to horseback riding beneath wide Kansas skies, feeding a lifelong love of the untamed West. His father was never available to him, and Larry chose not to know him—a decision born of silence, pain, and a burden he rarely shared. It was a silence Larry rarely spoke of, but it was there, tucked into the edges of his stories.

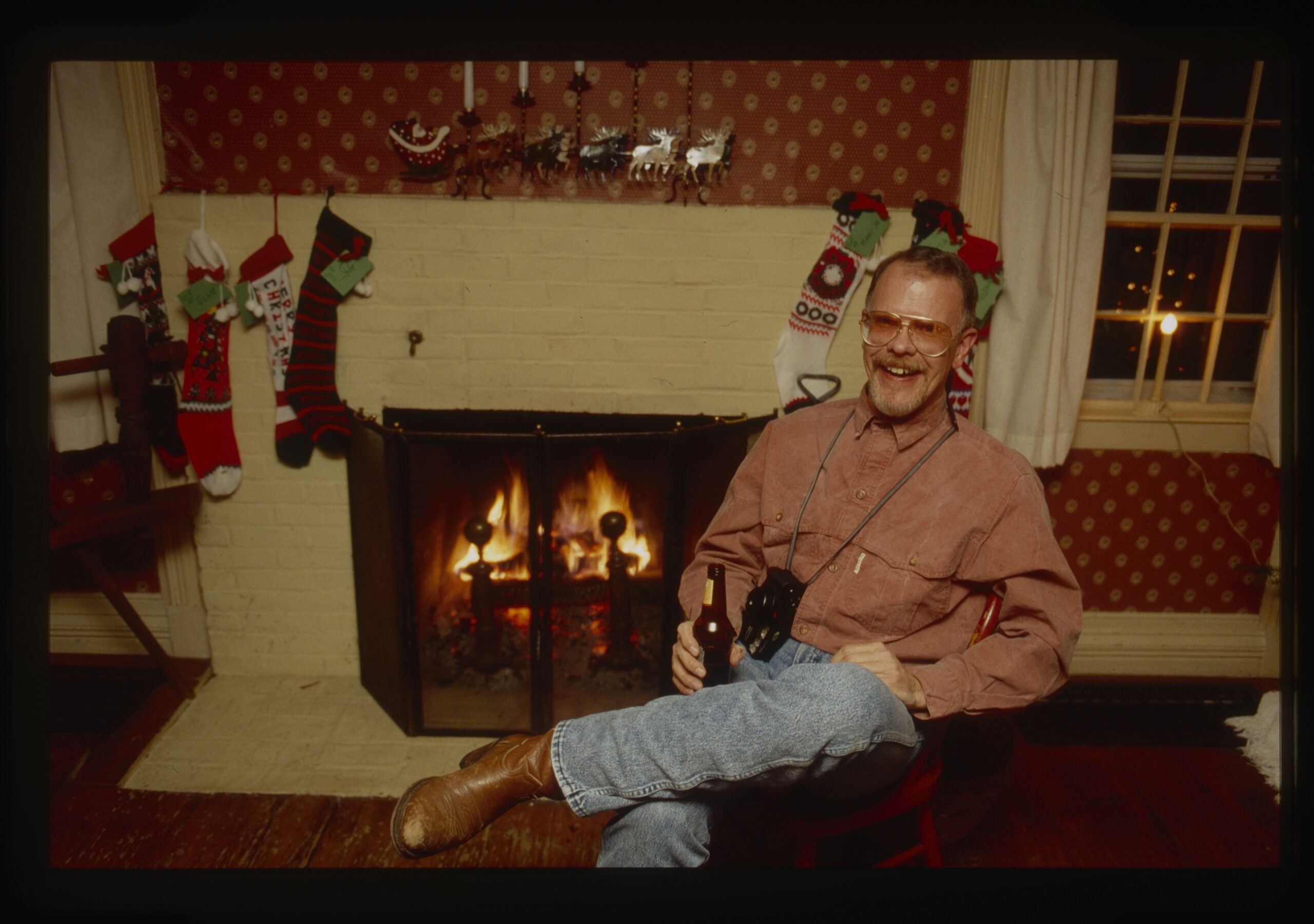

During his Army service from 1967 to 1971, he worked as a photographer—a skill that would shape the rest of his life. Afterward, he attended the Brooks Institute of Photography in California, where he studied illustrative photography and motion-picture production. He was a photographer first, taking up writing as a way to expand his magazine opportunities. Eventually, the pen matched the lens—and sometimes outshone it.

His Car and Driver stories were often masterworks, dispatches from a man who drove to find himself. As motorsport editor, he covered races like a war correspondent, not a curbside scribe. Even when he wasn’t covering races, he approached every road test like a battlefield dispatch—personal, immediate, alive. His 1987 BMW M3 review wasn’t about specs—2.3 liters, 192 horsepower, 0–60 in 6.9 seconds—but a moonlit canyon run, the inline-four “howling like a wolf,” the driver’s pulse racing with the tach. “This ain’t a car,” he wrote, “it’s a pact with the devil, signed in tire smoke.” He logged 5,000 miles in weeks, chasing Ford’s secret Mustang GTP, or swapping tales with racers like Bobby Rahal and Bobby Unser. No distractions—just the road, the car, and Larry: a conductor in communion with the machine and the moment.

Larry loved discovering roads. The best ones weren’t easily found on maps; they unfolded like secrets, each turn revealing a little more of the world and a little less of what haunted him. The cars mattered—deeply. They weren’t just vehicles. They were the keys to discovery, the partners that made the road’s promise real. He chased beauty everywhere: in women, in machinery, in the wide western vistas that drew him again and again, in the light slanting across a windshield at dusk. When he drove, he tuned everything else out—no radio, not even a glance sideways. The act of driving was sacred. It required total focus. It gave him peace. The deeper truth? Likely, Larry couldn’t trust people the way he could trust cars. Cars—good cars—were understandable in a way that most people weren’t.

He wasn’t built for everyday life. The domestic rhythms, the nine-to-five grind, the endless list of errands—even paying bills on time—overwhelmed him. He carried a frightened child inside, and driving kept that part of him safe. Everything had to be right. He would spend long, quiet minutes adjusting the seat, the mirrors, the wheel—seeking that perfect communion between man and machine. Sometimes fifteen or twenty minutes of tweaking and adjusting, until everything was exactly right. And when he found it, he became something more. Not just a driver, but a conductor. He could feel what the car was saying—its balance, its limits, its soul. It was as if the car became a second skin—every vibration, every tire scrub, every gear click flowing through him like nerve signals. He and the car became a matched team. When that connection was there, joy followed.

But that also meant he demanded greatness. All cars, he believed, were supposed to be great. Anything less was a disappointment. A betrayal. A distraction from the purity of the road. And worse, a bad car reflected poorly on the person who chose it. Flash over feel? Spec sheets over soul? Larry didn’t just judge the car. He judged you. The Corvette, for example, often left him cold—its numbers were there, but the feel was missing, often sacrificed to the squeaks and rattles caused by cost-cutting bean counters. It chased speed at the cost of sensation and soul, sacrificing the driver’s connection to the car on the altar of mere performance numbers. To Larry, that was unforgivable. A Ferrari 328, for instance, might look the part. But if it didn’t deliver that essential connection, it was all pretense. And pretenders had no place in Larry’s world.

Under David E. Davis Jr.’s command, Car and Driver entered its golden age—and during that time, three voices stood above the rest, sharing pages, deadlines, and the wheel: Davis himself, Patrick Bedard, and Larry Griffin. Each reached the level of true greatness, but each in his own way.

David was the magazine’s swaggering statesman and bon vivant—witty, worldly, always chasing the good life and taking you along for the ride. His writing didn’t just describe cars; it welcomed you into a broader world of taste, experience, and confidence. Patrick was the engineer behind the wheel and the typewriter—precise, unflinching, and proven. He didn’t just write about driving at the limit—he lived it, racing professionally and even competing in the Indianapolis 500. And Larry? Larry wrote from somewhere deeper. He didn’t just tell you what a car did—he told you what it meant. He wrote like a man who needed the road to survive.

And even then, Larry stood apart. Revered by his fellows at the magazine? Not quite. He was too peculiar, too internal. He stood too far removed from the rest. To some of his coworkers, he was just” Odd Larry”, or “Lawrence of Kansas”—the guy who wrote long, who needed editing for length if not content, who took cuts personally because he loved every word like each was his beloved child. But when his work hit print, the truth was clear: he was second to no one. Not when it mattered.

His reviews didn’t just assess a car’s performance. They felt like dispatches from a cockpit, mid-flight. Whether it was a road test, a trackside report, or a supersonic joyride, Larry brought the same voice—direct, vivid, poetic. He covered races like someone reporting from the edge of war, not the edge of a track. His account of riding in the back seat of an F‑4 Phantom jet, punching through Mach 2, read like scripture for speed. But whether the machine had four wheels or two wings, the tone never changed: he wasn’t writing about specs. He was writing about people chasing clarity and courage through speed and control—the kind that turns machinery into meaning.

And he affected people. He affected me. His January 1979 review of the Pontiac Trans Am didn’t just evaluate handling or performance. It was a requiem for a fading era—the last big-engined Trans Am. He wrote of it vacuuming “the leaves of autumn into vortexes that would chase us down little-known paths of pavement through deserted woods.” He described the big-engined joy of this era of Trans Am in its final year, about how this car “will not pass this way again.” Most road tests measure what a car does. Larry revealed what a car meant and how communing with it felt.

That article lit a fuse in me. Some years later, still guided by the power of his words, I bought a very similar Trans Am, optioned just as he had described. More accurately, as he had prescribed. I chose one with the stoutest engine, the mighty W72 400, but without air conditioning. Larry had taught that the air conditioning “would’ve added 108 pounds, most of it over the front wheels, and it would’ve dragged on the engine like a lifetime of tar and nicotine, three packs a day.” Sacrilege. Larry had rhapsodized about this magical conveyance’s handling, describing how it was to be “skating at 100 or 110, adjusting in increments with throttle and wheel, balancing, playing a slick nibbling ragtime on the tires, calling up a reservoir of power oversteer to expel yourself from the classroom of one corner to the next, always learning but never left behind.” Reading that, at the ripe old age of 11, I finally knew what being alive would feel like. What I had to chase in life.

So when I bought my Trans Am and used it as my very own school of high-performance driving, I worked hard to become good enough that I too could one day commune with this great car as Larry had. Not that I would be as good as Larry. That wasn’t likely. Both his admirers and detractors will admit, often grudgingly, that amongst all the drivers in that golden age of automotive journalism, Larry was the best. But matching him in skill didn’t matter. What I wanted—what I craved—was to feel what he had. So I worked hard, honed my skills, and waited for the moment. And when it came—that first clean, high-speed, oversteering slide—the world slowed. The rear swung out smoothly, predictably. We danced on the edge. Not just me and the car, but me and the words. I wasn’t imitating Larry. I was feeling what he had felt. It was thrilling. Frightening. But mostly it was confirmation. I belonged. I finally understood. I was alive.

That car—and Larry’s prose—started something deeper. It led to Larry-Griffin.com: a tribute, an archive, a small fire left burning for a writer too many have forgotten. Larry had millions of readers once—most moved on. But for a few of us, his words never stopped echoing. He didn’t just write about cars. He made us feel them. And once you’d felt it the way he described it, you couldn’t go back.

I owe him more than admiration. I owe him thanks—for the lessons, for the beauty, for the photographs that caught what words couldn’t, and for sharing, out of his own quiet struggles, something that became a kind of home and compass for the rest of us. For inspiring my end-to-end drive of Route 66. Inspired by, and dedicated to, him. Because what he gave us wasn’t just about machinery—it was about roads. About freedom. About challenging ourselves and discovering who we are. Testing ourselves to see if we were good enough. About chasing horizons we didn’t know we needed until he showed us where to look.

Larry Griffin was the real thing—flawed, brilliant, private, pained, poetic. He chased light through a viewfinder and truth through a throttle. But he was built for the road, and for those rare moments when everything works.

When pneumonia claimed him on March 15, 2008, in Independence, the automotive world lost a voice that made asphalt sing. Buried in Mount Hope Cemetery, where he once drifted a florist’s Ford Fairlane as a teen, Larry left stories and images that still burn bright. And though his writing once reached millions, today he lingers mostly in memory, in yellowing clippings, in the hearts of those who saw him. Like the machines he loved, he wasn’t built for forever. He wasn’t just a writer or photographer—he was a poet of the road, chasing horizons to find the peace and beauty his soul craved.

Flawed, brilliant, private, pained, poetic—Larry Griffin was the real thing.